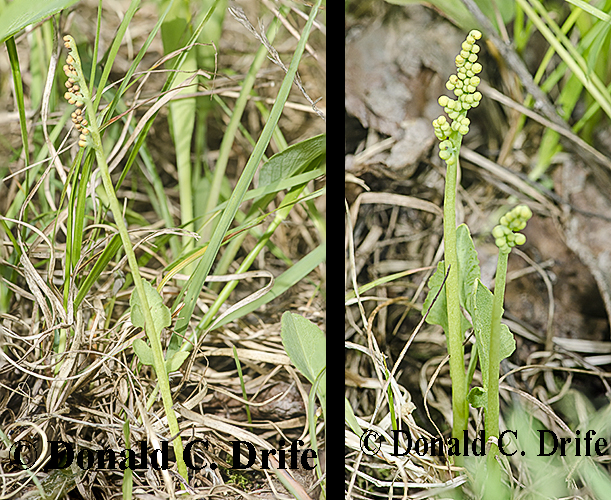

Recently I found two species of Bird’s Nest Fungi growing on wood chips. Although they are small and their brownish or grayish color allows them to blend in with the mulch; they are easily found because they form large groups.

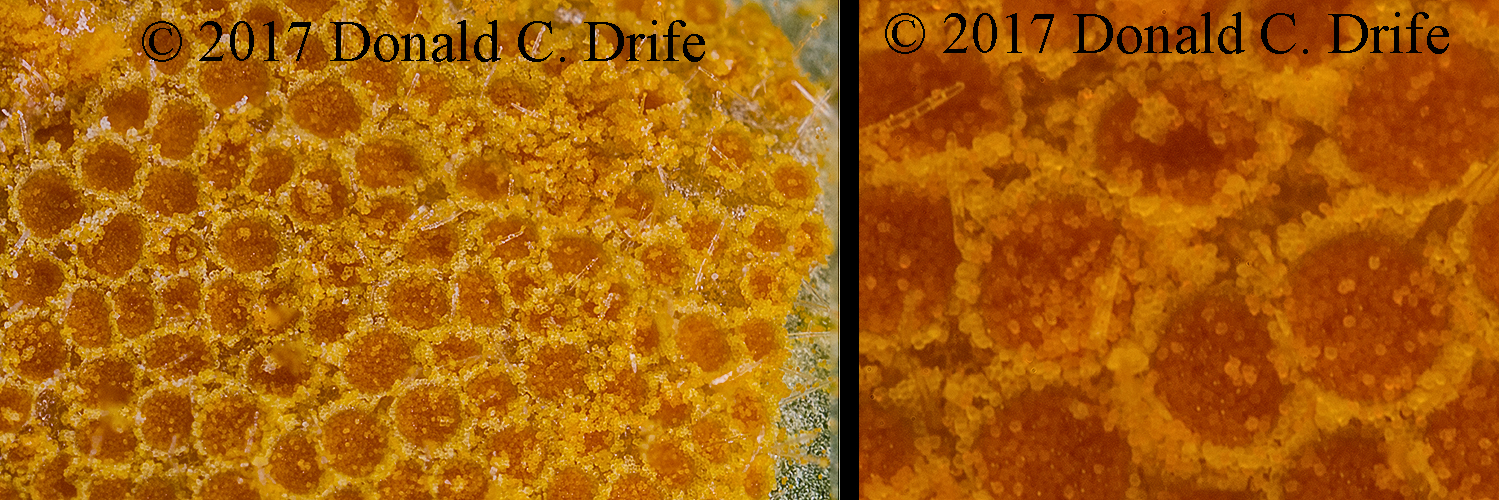

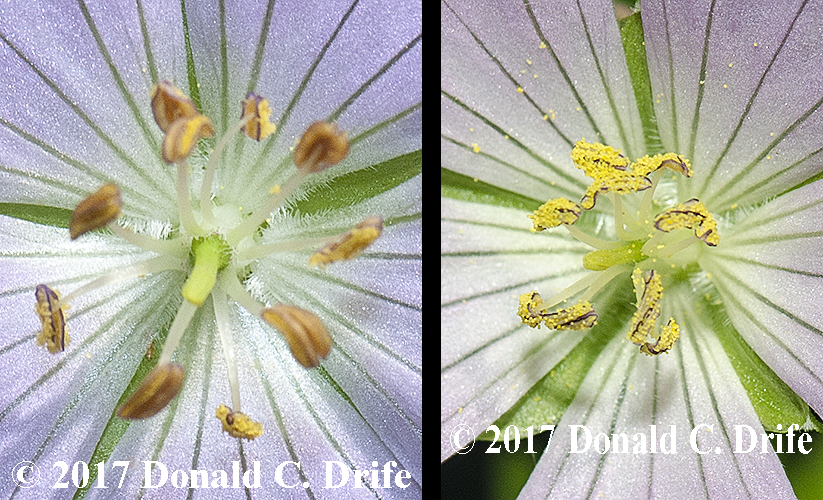

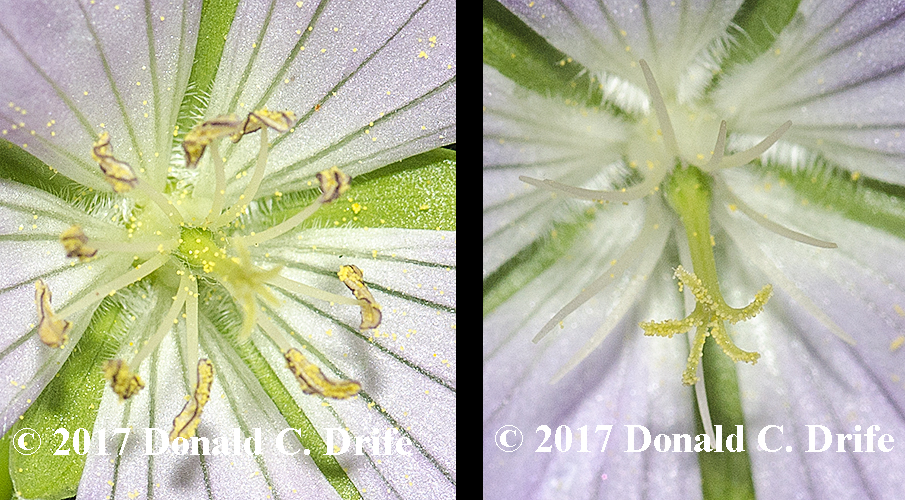

They do resemble a tiny bird’s nest complete with eggs. The egg is a peridiole, its stalk is called a purse, and the nest is called a peridium. Rain ejects the peridiole and shatters the purse exposing an inner cord (the funicular cord) with a sticky pad (the hapteron) attached to the loose end. This pad adheres to a plant or other solid object elevating the peridiole. When the peridiole dries it splits releasing the spores. The peridiole contains the spores and resembles a tiny puffball. The periduim is capped with a lid known as an epiphragm. It disappears as the spores ripen and prevents immature spores from being discharged by rain. I attempted to discharge the peridioles by applying water from and eye dropper into the splash cups. It did not work.

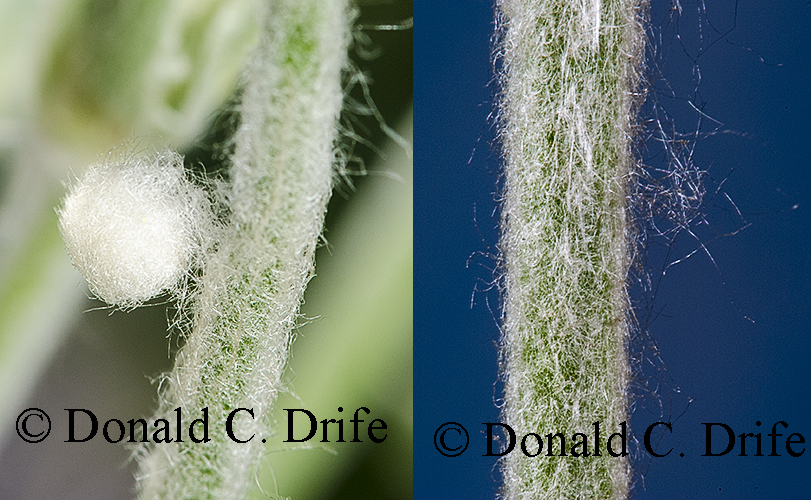

Fluted Bird’s Nest (Cyathus striatus) occurs world-wide. The eggs are gray. The inside of the nest is fluted and its outside is covered shaggy brown hairs even when old. The lid is hairy when young and sheds the hairs just before it disintegrates. Dung Nest Fungus or Dung-loving Bird’s Nest (Cyathus stercoreus) occurs around the world. Although the common name is Dung-loving I find it on wood chips. The Latin word stercorarius means of filth” or “of dung.” The eggs are shiny and black. The inside of the nest is gray and smooth while the outside is brown and shaggy on developing fruiting bodies but it becomes smooth with age. The lid is thin and white. Some botanists state that animals eat plants with attached peridioles, and expel the spores in their dung.

Bird’s Nest Fungi in North America north of Mexico comprise approximately 30 species in five genera. All of them are in the family Nidulariaceae. Check out Michael Kuo’s key to the bird’s nest fungi at mushroomexpert.com to identify other species.

Copyright 2017 by Donald Drife

Webpage Michigan Nature Guy

Follow MichiganNatureGuy on Facebook