Eastern Fox Squirrel

January 21 is National Squirrel Appreciation Day. Christy Hargrove, a wildlife rehabilitator, began the celebration. Mid-winter is a time when food becomes hard to find for our squirrel friends, so she felt that it was a good time to focus some attention (and food) on them.

Michigan has five species of squirrels. Northern and Southern Flying Squirrels (Glaucomys sabrinus and G. volans) are nocturnal and shy. I hear them calling on dark nights and seldom see them. The most reliable way to distinguish the two flying squirrel species is by their teeth. Both species are recorded from Oakland Co., Michigan.

The other three squirrel species are well known and often observed. They are Eastern Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger), the Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) including the Black Squirrel, and the much smaller Red Squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus).

Eastern Fox Squirrel

The Eastern Fox Squirrel is the largest of our Michigan squirrels, 50-56 cm. (20-22 inches) long and weighing between 680 and 1360 grams (1.5 and 3 lbs). It differs from our other squirrels by its size and yellowish brown, with some reddish color. There are some color variations, including individuals that are much paler than normal. I have seen pure white albinos with pink eyes. This species and the Eastern Gray Squirrel both build leafy nests in trees and will use cavities in trees for nesting as well.

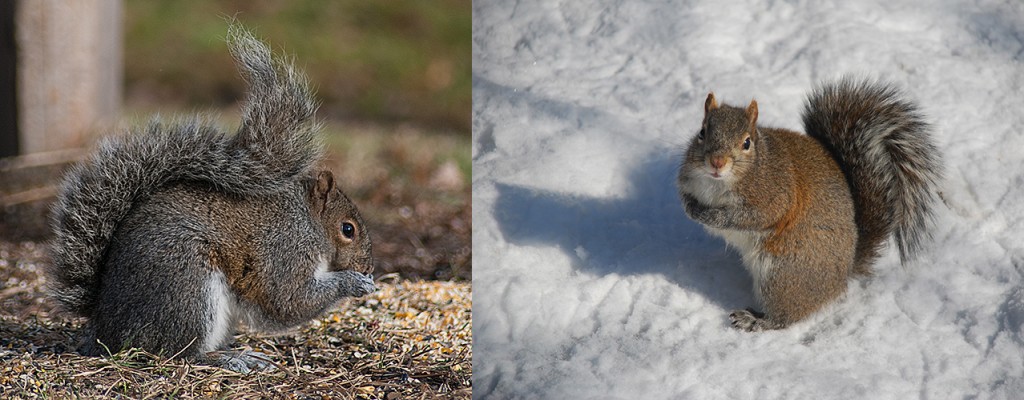

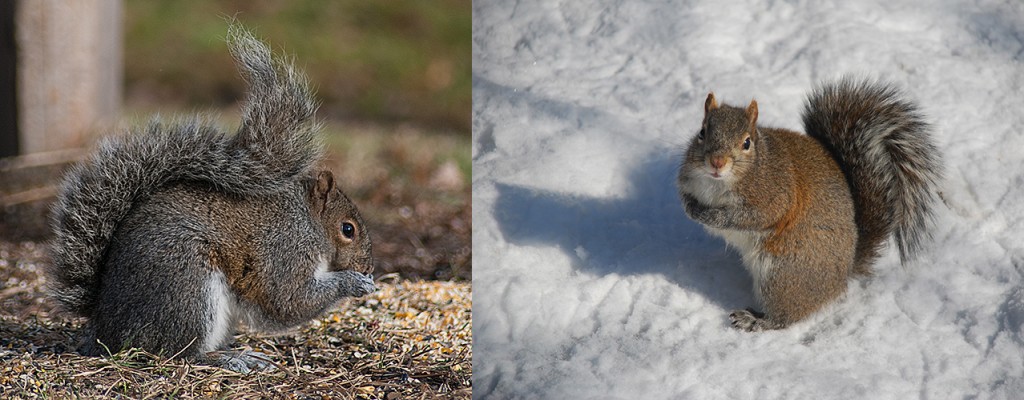

Eastern Gray Squirrel grey morph

Eastern Gray Squirrel black morph (Black Squirrel)

Both gray and black squirrels in Michigan are members of a single species, the Eastern Gray Squirrel. Ranging from 41 to 51 cm. (16 to 20 inches) long, and weighing between 340 and 680 grams (.75 and 1.5 lbs), it is slightly smaller than the Eastern Fox Squirrel. The gray morph is dark to pale gray on the back, with a light gray or buff belly. Some of the black morph animals have blond tails or reddish coloring in places. Though they appear very different, the two color morphs are often present in one litter. According to the Animal Diversity Web entry for this species, the black color morph is more common in the northern part of the squirrel’s range. Black animals lose less heat and have a lower basal metabolic rate, which should give them a survival advantage in cold winter temperatures.

We now see many Gray Squirrels in both color morphs in our yard. When we first moved here 22 years ago, there were only Eastern Fox and an occasional Red Squirrel. The Gray Squirrel has spread into the area and become dominant over the Fox, even though it is smaller.

Red Squirrel

The last squirrel in our area is the Red Squirrel. It is small, 28 to 35 cm. (11 to 14 inches), with a reddish back, white underside and broken white eye-ring. Even though it is smaller, size matters not. It is aggressive, and can and will run off larger squirrels.

Get out and watch squirrels. They are fascinating. One of the Fox Squirrel photos shows a squirrel on a garbage can that contains sunflower seeds. It was pulling on the chain trying to break in. They sprawl out on our deck railings to cool off on a hot day. They fluff up their fur in the cold and hold their tails over their bodies in the rain or snow. They run and jump through the trees. They are just fun to watch. Have a happy NSAD.

Copyright 2014 by Donald Drife

Webpage Michigan Nature Guy

Follow MichiganNatureGuy on Facebook