While I was raking leaves off our small “lawn,” my wife (knowing full well the answer would be yes) asked me if I wanted to see a leaf gall. It was formed on the petiole of an Eastern Cottonwood (Populus deltoides). I checked bugguide.net and identified that a Cottonwood Gall Aphid caused the gall. Poplar Petiole Gall Aphid is another common name for this species.

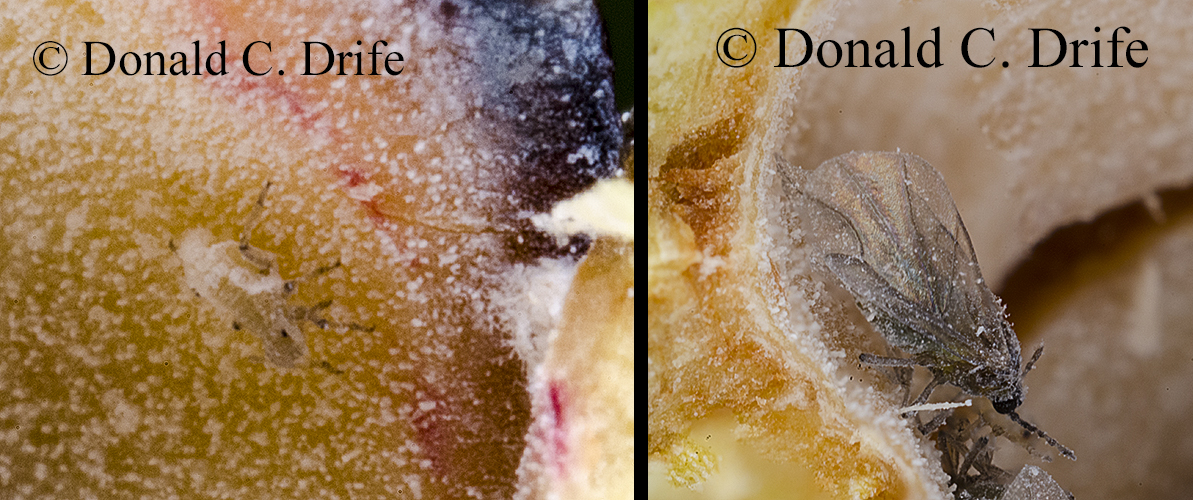

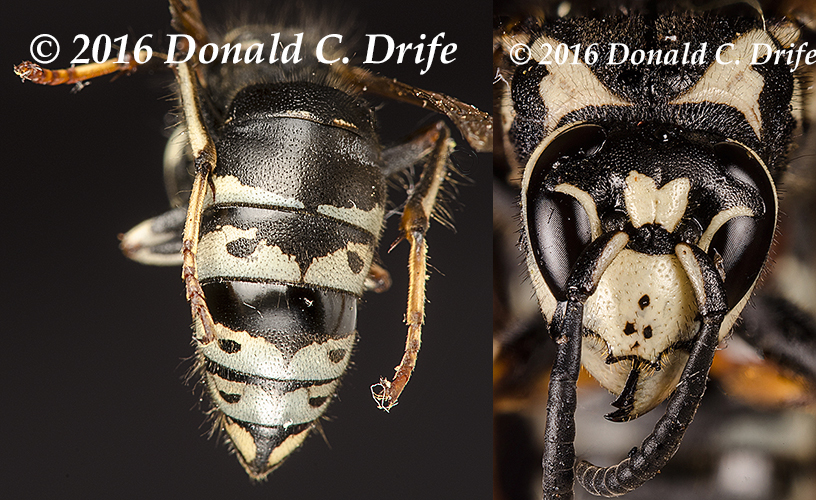

It is a hollow gall, not quite round, with a transverse split. It occurs along the petiole (the stem of a leaf) just below the blade. I cut a few open and found a waxy substance but no insects. They might have exited through the slit. I opened one more and found the adult aphid.

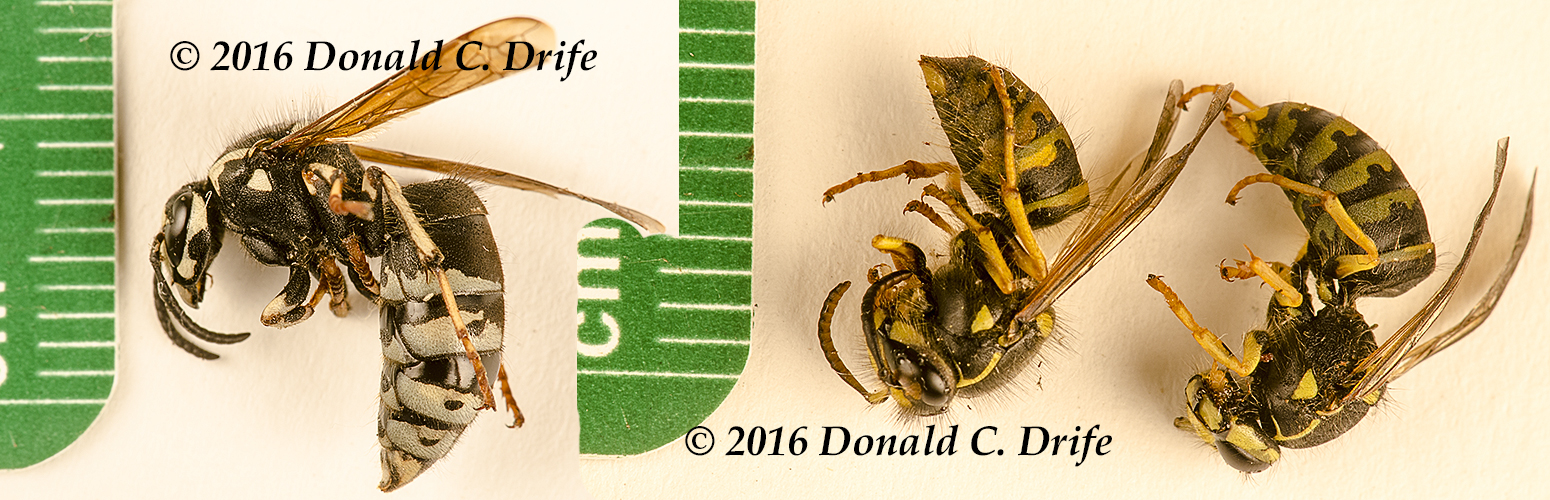

I Googled the scientific name and the phrase “life cycle” and found Roberta Gibson’s informative and fun blog “Growing with Science (The Poplar Petiole Gall Aphid was the “Bug of the Week” in May of 2015.) She explains the aphid’s life cycle. Aphids seldom have straight forward life cycles. They over winter as eggs on Cottonwood twigs. They hatch in the spring and feed on the leaf petioles, causing the plant to produce the gall. Then the insect moves inside. It becomes a winged adult and exits through the slot in the gall’s side. They complete their life cycle on the roots of cabbage, turnips, or another member of the mustard family (Brassicaceae). Another common name is Cabbage Root Aphid. The aphids complete their life cycle by flying back to Cottonwoods and depositing eggs on the twigs or bark.

This is a great time of year to look for galls. Get outside and enjoy Nature. Also, check out Roberta’s blog and website. Even though she is based out of Arizona many things she writes about occur in Michigan.

Copyright 2016 by Donald Drife

Webpage Michigan Nature Guy

Follow MichiganNatureGuy on Facebook