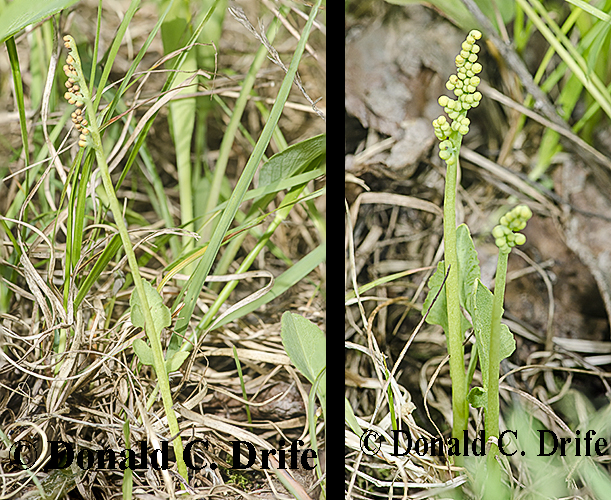

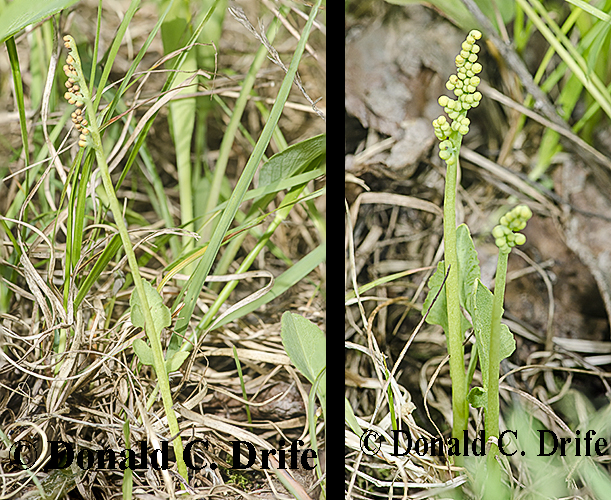

Moonwort habitat – L Daisy-leaved Moonwort – R

Moonworts or Grape Ferns are small ferns. Most are less than 10cm [4 inches] tall. Herb Wagner called them “belly plants.” They have a vegetative blade, called a trophophore, and a separate fertile segment, called a sporophore. Sporophores resemble tiny clusters of grapes hence the common name. Characteristics of the vegetative blade help to distinguish the species. As you learn the plants other subtle features become apparent such as the color of the plant, timing of spore dispersal, and branching of the fertile segment. The Michigan Flora website has a workable key and range maps. Another great resource is Dr. Farrar’s work found on the Ada Hayden Herbarium website. This site includes species treatments of all of our Moonworts.

Moonworts grow along stable sand dunes or in fields that have had mild disturbances. I find them growing under Wild Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) or Apple (Malus spp.) trees with Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron spp), Sheep Sorrel (Rumex acetosella), Hawkweed (Hieracium spp.), or Wild Strawberry (Fragaria spp.). These habitats are not where most botanists look for native ferns. They also grow along stream banks and along deer paths and old dirt roads through woods. The plants cannot withstand competition from other vegetation and require some type of minor disturbance in order to survive.

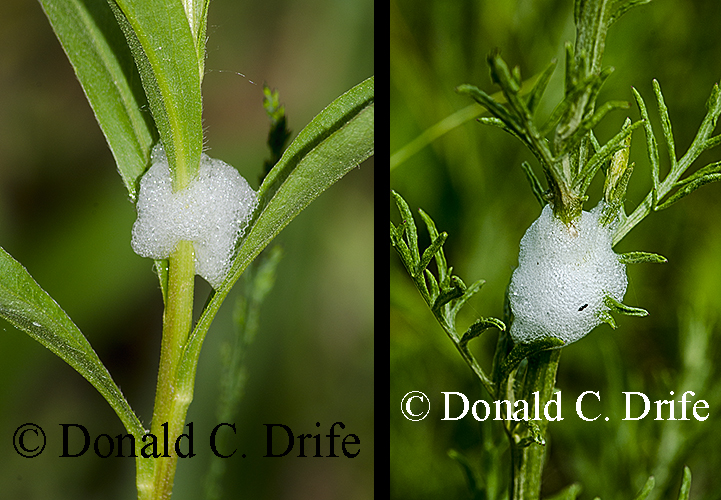

Daisy-leaved Moonwort (Botrychium matricariifolium)

When I began studying this genus there were five species known from Michigan. Now there are eleven species and perhaps one more still unnamed.

Least Moonwort (B. simplex)

I recently visited a colony that once had seven different species but now could only find Daisy-leaved Moonwort (Botrychium matricariifolium) and Least Moonwort (B. simplex). Dense grass moved into this old orchard choking out Moonworts. At one time there were 15,000 individuals in this colony. Now there are no more than 500 plants. The National Guard used this field for helicopter gunship firing which tore up the sod slightly, allowing the plants to flourish. After we discovered two threatened Moonworts species, Michigan Moonwort (B. michiganense), and Prairie Moonwort (B. campestre), the Guard discontinued firing to “protect” the area. Currently the sod is too dense and Moonworts are dying out.

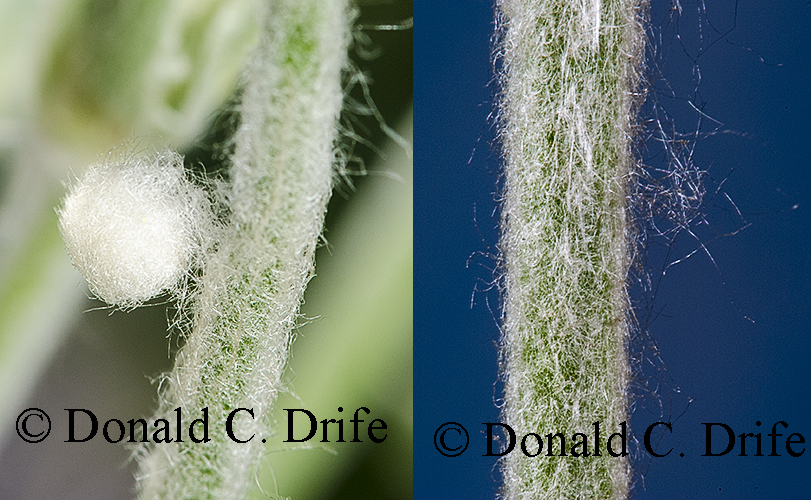

Mingan Moonwort (B. minganense)

In the 1990s we discovered a colony of 20,000-30,000 Moonworts along ten miles of forest service road in the Upper Peninsula. We visited the area in 2003 and noticed that the road shoulders were growing up. Last weekend we found about fifty plants of four species, Daisy-leaved Moonwort, Moonwort (B. neolunaria), Mingan Moonwort (B. minganense), and Spatulate Moonwort (B. spathulatum) along the road. Plants occurred mostly on sandbanks kept a little raw by erosion. Lumbering is not happening in the area so road grading is not disturbing the road shoulders and keeping them open.

Moonwort (B. neolunaria)

Moonworts are more difficult to find now than they were 25-years ago. Tony Reznicek stated that Michigan’s open areas are growing up. I believe he is correct.

For such an inconspicuous plant a great deal of lore surrounds it. If you place a Moonwort into a box and leave it overnight it will produce silver. Herb and I tried it and it did not work. Herb said it would have been easier than getting National Science Foundation grants. Moonwort opens any lock that its spores are placed into. If a horse walks over a plant it will throw a shoe. It is also an ingredient in several love potions.

June and July are the best months for hunting Moonworts. Most species disperse their spores and wither away before August. Get out and look for plants. They might be difficult to identify to species but they are still fun to find.

Copyright 2017 by Donald Drife

Webpage Michigan Nature Guy

Follow MichiganNatureGuy on Facebook